The Prom

I have posted infrequently over the last few months, but that may change this year. Not exactly a New Year’s resolution, more a sense that 2012 will be more creative. I finished 2011 with a week’s holiday at Wilson’s Prom. If that doesn’t immediately conjure for you beautiful surf beaches, peace, the reed-lapped river, birdsong… well, I hope you have an alternative paradise somewhere in this world.

Here are some poems I wrote while I was there. By the way, I’m currently reading Stephen Fry’s book, The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking the Poet Within. He’s very funny – which is a bonus in an instructional text – but is also teaching me a lot about writing verse. For those poets who already know about and appreciate (and perhaps even positively demand) close attention to poetic style, iambic pentameter and all, please forgive the lack of education so evident in my Prom poems. I hope you enjoy ’em anyway.

Forgiveness

I woke up fuzzy, full of doubt and fear,

But I went for a walk from Tidal River to Picnic Bay,

Waded through shales of gold leaves in tea-tree tunnels on possum-soft dirt,

Looked out over clear waters to seaspray islands,

Climbed over rusty granite boulders,

Carrying my thongs in my hand,

Pricking my soles on tiny shells,

And the wind polished my face with salt crystals

And there were warm holes in the shallows

And the sand at Squeaky Beach squeaked underfoot

And we did indeed have a picnic of cashews and water,

So I came back loving you and the world again.

*

Norman Beach

A wide chunk of fair sand –

Endless walk to the water

Lapping up against the luminous rock

Under a gentle sky.

If this were Hawaii, we’d be ‘Excuse me, excuse me’

– just finding a place to sit!

And there’d be radios and neon surf shacks and shit.

But there are instead a few families and the surge of waves

And the tea-coloured stream flowing out to meet the green under the busy eyes of gulls

And space.

*

That

There is a spot in my mind

That I can almost see

That feels like something good and peaceful

That is beyond my talk

That lies beyond wondering

That is just that.

*

A man and his child

A young man carried a baby on his hip. He, the man, was frowning and looking for something – his wife, his thongs in the sand, his next meal, his God, I don’t know. All the while, the baby bounced along, smiling under her downy hair and chatting to her dad who was busy searching. She, the baby, laughed in recognition of me, another person who was interested. I thought, how wise the one, how young the other.

*

Birds

A cockatoo took to the wind above the river,

alone and silent,

home hunting,

flight flapping

on butter-tipped wings

While I benched on the path below,

green-grassed and grieving

watching, wishing, in wingless unbless,

for a crash-landed past.

*

Two blue wrens hip-hopped

Among the reeds

Sway bopping

On bent bows

Of woodwind grass

To the wind’s upbeat.

*

Photo: The photo was taken at Wilson’s Prom by photographer and fellow-scribe, Bob Thornhill.

Not quite home

All my life I have lived within the compass of these desert horizons. I know there is a different world outside because I have twice been to a city and once – when a very small child – to the sea. Of course, there are other ways to know, but they are fading and my memory is sufficient.

All my life I have lived within the compass of these desert horizons. I know there is a different world outside because I have twice been to a city and once – when a very small child – to the sea. Of course, there are other ways to know, but they are fading and my memory is sufficient.

The sea was a field of mid-spring spinifex grass when the ears wave and waft seed on the breeze.

It is only five years since I visited the city; that place a week’s journey away through narrowing hills and widening roads. Minny brought me. On the way, we dined at the hotel in which her mother and I stayed on our honeymoon night. The steaks were not as thick or tender as formerly. There is a motel attached to the building now, but Minny and I chose instead to drive on until we found cheaper lodgings. My journey was in order to negotiate the sale of my farm, a time of loss, and I needed to watch pennies in case the sale went badly.

The brumbies in my mind did not keep pace as we swept up to those tower blocks on the horizon and then in between them at last. Since my previous visit as a boy on vacation, I had forgotten the frequency of traffic lights and young people and recalled more chimneys. My thoughts only fitfully held the real things of my life – the flaking of fence posts, the scent of cattle sweating in the sun – as we entered those streets with rough haste. Many of the real things were soon not to be mine, but my main regret was that I could not give them over to Minny, as my father had handed them to me so long ago in a sheaf of papers marked ‘Grant of Land’. He had been rightfully proud; a man who started out with a small parcel of unwatered pasture able on his retirement to assign the duty of caring for fertile river flats and 1,000 head of stock to his eldest.

I apologized aloud to Minny and silently to her dead mother as we entered the glass doors of the lawyer’s office. Minny only shook her head. What does a divorced librarian need with a stony creek bed and a pile of rusting sheds anyway? That was the sum of her argument. It was not my fault, so she also told me, and it is true enough that the banks’ takeover of our district followed the drought’s own land grab with relentless and logical precision. My memory of healthy grass plains should be consigned to the dead past along with my vision of the sea. This I cannot deny, but regret is taught by the heart rather than reason.

And so I came home from that last urban venture, if not quite home. At least, I ended back between the sky walls I’ve always known. My unit – not yet a berth in a nursing home – is close to the municipal offices where Minny works, and she drives me past the farm gate on weekends. The distance is forgiving out here. It lets you abide in wide circles without making you fear you have strayed too far. From different hills, you can see the same bird wheeling.

I shelter now, rather than live, and perhaps sheltering is better. I am in the hands of God the earth, God the sky, God the wind, and He has not yet scattered my bones, which are still strong enough for the little work I have to do. I have gained rather than lost my sense of His presence, being much alone and usually idle. I hear his voice in the crow’s cawing and the thud of hooves. The silence that calms shy animals also gentles me. Human chatter has never been my craving.

I have no need for tools now, except lowly ones that I keep about my person. A sharp knife is still a good thing. I skinned a rabbit for my grandson this morning and, while wiping the blood on the ground, recognized the drops of it. It was the dewy bare soil that ran through my father’s fingers as he planned new pastures, and the oil from the diesel train that came to rest forever in our siding years ago, and the flower of the bottlebrush tree that perhaps still grows outside my kitchen window, and the black grease around the eyes of my first working dog. And it has stopped flowing.

Sometimes I wake from dreams of death by dust. It is clogging my throat, my lungs, my veins. Who will heed my gasps?

Let me not die in my bed but while I am out walking somewhere, please God. Let my body lie between walls only of weather. Let me feel the cold wind on my face and the bite of rain on my bare arms, at the end. If I hear the voice of the grass in the breeze, I will be comforted.

But I am become feeble-minded indeed if I give in to fears cast up by nightmares. This compass of horizons – and the years it has been my lot to carry – mean no more to the universe than a set of hopping footprints among the spinifex. Let me, instead, accept the passing. There is no call for mourning. God’s tears do not fall, and neither shall mine.

Thanks for reading my story.

Photo: Yaruman5

The word as visual art: Is Wordle the last word?

It’s true: words really can be art. We know they should sound good to the inner ear, but how about making them pleasing to the eye? Words, after all, are symbols, representations of meaning – and they can be represented in many ways. The visual representation can influence the meaning.

A friend of mine recently indulged in NaNoWriMo and was introduced to Wordle as a reward. (I say ‘indulged’ because I’m envious; he wrote a 50,000 word novel in a month.) Wordle is a quick easy way to turn your words, and anyone else’s, into a word cloud picture. You can:

frame it…

stencil it…

cover a book with it…

paper the walls with it…

create a Powerpoint presentation of it…

write a poem about a loved one, Wordle it and send it to them as a card…

make an ad with it…

turn your 50,000 word novel into it??? I wonder…

Here are some Wordle examples to inspire you:

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

But you’re doubtful, aren’t you? You’re thinking Wordle is too quick and easy. Where’s the evidence of skill, of mastery, of sweat, of commitment, damn it? In a Wordle, the meaning just might translate as I-couldn’t-be-bothered. Fine, then. Go ahead and learn calligraphy, buy your parchments and your gold leaf.

If you want to know what real commitment to words looks like, check out this example below:

This photo was taken on Australia Day, also known as Survival Day, 26th January 2008, the day the Australian Prime Minster said sorry on behalf of the nation to the ‘stolen generations’ of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s Sorry Speech was, in itself, an important piece of word art. It was heartfelt and healing, and it took ‘sorry’ to a whole new level of meaning as a nation-definer. I still can’t read it without crying.

x

x

And what do you think of word tatts? Every day, your body is talking to you and everyone else who sees you. It says the same thing, over and over again…

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

In the context of the tattoo above, Kurt Vonnegut’s words become a philosophy of life.

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

The tattoo above is Hebrew scripture. David, before he became king, asks that his enemies will fall by the sword and become no better than foxes. The meaning here is ambiguous. Why would you wear this biblical line as a tatt? Perhaps to show political allegiance, but it might also signify devotion to a spiritual path, even more so than a Hijab or a Christian cross both of which can be taken off.

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Don’t panic – we’re in this together. I think this tatt is my favourite, especially as it has a greater impact in a group.

I realise now that this post could also have been titled: What to do with your work if you can’t get a publisher and are still resisting the bottom drawer/delete button/shredder.

Photographers’ flickr pages:

Purple Slog, London Looks, Ged Carroll, Dave Keeshan, Molly Germaine, Leah Jones, Leo Lambertini

In the end they sent an application for renewal of dog registration and I had to answer. It was just like The Truman Show. Every which way, I was hounded (pun intended). The people of the world with their ways, they were out to get me, no doubt about it.

I didn't make this up. Zoom in on the sign in the sky. No creative editing here, I promise. Punt Road, Melbourne as one strange art gallery.

I was out walking the dog and I saw a sign above the railway bridge. It read, ‘Blame and punish the individual.’ Beneath the sign, cars streamed into the tunnel and out of it, turning left and right, waiting at the lights, revving a bit as they waited. On the bridge, people waited for their trains, the 5.36 from Frankston and the 5.12 – running late – from Epping. No one looked at the sign, although it was huge, at least the size of a large plate-glass window in an art gallery. White letters on a black background. A big full stop the size of a basketball after the word ‘individual’. No one looked at the sign because they didn’t need to. They all knew it, they got the message, they were all breathing it in anyway. Individuals being blamed and punished, and doing their fair share of blaming and punishing too.

Lucky dogs can’t read, I thought as I looked down and shook my head. The dog was wagging her tail. She likes cars as long as she’s on her lead. She knows she’s safe with me.

On the way home, I passed another sign that gave me pause. See? The world is not that real, don’t worry, I told the dog. She clearly wasn’t worried at all.

But then I got home and discovered that her registration was up for renewal. Now there’s a sign that you can’t ignore. She runs away, the Council finds her, they’ll be on to me with a fine, and who wants that? I could risk it, and it’s not that much money anyway, but there are some ways of the world that you might as well go with. The application letter said she was a small Australian Terrier, black, with no distinguishing features. The only part that’s strictly true is the part about no distinguishing features. It’s also the only part she’d appreciate, if I could tell her. She’d like that description of herself, I think.

She wears a green tag on her collar, an extra tag, not just the one the Council gave me. It’s because she does run away occasionally. An adventurer, she is. A covert adventurer, which is why she likes to be indistinguishable. Goes out into the world, looks at its ways, and then comes home. Always comes home. I like that in a person, the homing instinct. That’s the bit that’s most true, and it’s what matters most about this whole thing, I guess.

The Cloud Street of life

Thousands of people claim Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet as their favourite novel. It’s certainly one of mine. But what is so special about this saga of two poor families living mid-20th Century in a rundown house in a parochial Australian town? The lives involved would probably rate as not worth the bother to most storytellers. Special? Winton’s characters live, die, fall in and out of love, get married, have kids, get old. They have their tragedies and their joys, mostly private ones, like most of us. But you wouldn’t give any of them a second glance on the daily train commute. In the course of 20 years, not one of them has a story that would make the front page of the newspaper you’re reading. Sure, they have their little sensations, but you’d mostly dismiss those as pub talk. So why?

Thousands of people claim Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet as their favourite novel. It’s certainly one of mine. But what is so special about this saga of two poor families living mid-20th Century in a rundown house in a parochial Australian town? The lives involved would probably rate as not worth the bother to most storytellers. Special? Winton’s characters live, die, fall in and out of love, get married, have kids, get old. They have their tragedies and their joys, mostly private ones, like most of us. But you wouldn’t give any of them a second glance on the daily train commute. In the course of 20 years, not one of them has a story that would make the front page of the newspaper you’re reading. Sure, they have their little sensations, but you’d mostly dismiss those as pub talk. So why?

Tim Winton opens up their lives for us as if that dusty broken old house on Cloud Street is a stuffed-full keepsake chest.

… an enormous, flaking mansion with eyes and ears and a look of godless opulence about it…

… the quiet yard where vegetables teemed in the earth and fruit hung, where a scarfaced pig sang sweetly at the sky…

He treats each member of the Lamb and Pickles clans as a soul who cradles the essence of life itself. Their every gesture is worthy of reverence simply because they are human beings.

Lester and Oriel Lamb are Godfearing people. If you didn’t know them you could see it in the way they set up a light in the darkness. You’ve never seen people relish the lighting of a lamp like this, the way they crouch together and cradle the glass piece in their hands, wide eyes caught in the flare of a match, the gentle murmurs and the pumping, the sighs as the light grows and turns footprints on the river beach into longshadowed moon craters. Let your light so shine.

Rose sharpened all her pencils and kept her writing desk in good order. Each drawer was neat as a diagram inside: paper, nibs, clips, crayons, blunt scissors closed like a body in repose. It was the way she’d have her whole kitchen, if she ever had one to herself: her whole house.

He doesn’t romanticise their lives. He keeps them complicated, knotty. He mingles their joy with sadness, refuses them important, let alone happy, endings. Yet he also treats them with so much compassion that you learn to revere them as he does. Fish Lamb, Cloudstreet’s central character – the most odd, disabled and beautiful of all Winton’s characters – voices his creator’s and our own feeling about them: ‘… you can’t help but worry for them, love them, want for them…’

And I’m excited about the mini-series of the novel, screening soon. The posters give hope of a thoughtful production. The still photos of plainly dressed characters and simple scenes are carefully designed. They’re pretty and polished, not flashy and false. Historical accuracy has not been compromised, but neither has the richness of these fictional lives. It looks like the producers might share the general respect for this novel. And many of us agree that it is the great Australian novel.

And I’m excited about the mini-series of the novel, screening soon. The posters give hope of a thoughtful production. The still photos of plainly dressed characters and simple scenes are carefully designed. They’re pretty and polished, not flashy and false. Historical accuracy has not been compromised, but neither has the richness of these fictional lives. It looks like the producers might share the general respect for this novel. And many of us agree that it is the great Australian novel.

But still, why so special? Why so great?

I think it’s because Tim Winton’s vision of life is the one we all want. We want to see our own lives in the same kindly light, no matter our foibles and our ordinariness. Look how he paints conversations, as if each word is the perfect and only thing that can be uttered in that moment. Not a word too many, not one too few:

Dolly rests an elbow on the sill. The grass is shin high out in their half of the yard. Bits of busted billycarts and boxes litter the place beneath the sagging clothesline.

I dunno what I’m doin, she says.

Do you ever?

She shrugs. Spose not. What about you?

He takes a drag. I’m a bloke. I work. I’m courtin the shifty shadow. That’s what I’m doin.

This is another life.

It’s the city. We own a house. We got tenants.

Do you remember Joel’s beach house?

Sorta question is that?

That was our life.

It’s easy to forget how beautiful Tim Winton’s style is. So many writers, particularly we Australians who are proud of the guy, model our work on his. ‘Wintonesque’ is already in the lexicon and will probably make it into The Macquarie Dictionary in time. We’re used to it is all.

Like all great books, there’s a message in Cloudstreet that readers can take away to enrich their own lives. It’s that we can have that same vision and it will redeem us. We don’t have to strive for worldly greatness or stand out from the crowd. We can be – and no doubt most of us are – no better or worse, no more or less important, than a Sam Pickles or an Oriel Lamb. All it takes is a little forgiveness, and our lives will be as lovable.

A story: Black, white, blue

He had white hair and blue eyes and was about 6-years old. I say ‘about’ only to take into account that many 4-year olds and 8-year olds could pass for 6. ‘About’ is a habit. Actually many people could and did pass for him. I’ve seen literally hundreds of lookalike photos.

He had white hair and blue eyes and was about 6-years old. I say ‘about’ only to take into account that many 4-year olds and 8-year olds could pass for 6. ‘About’ is a habit. Actually many people could and did pass for him. I’ve seen literally hundreds of lookalike photos.

There was one of a 53-year old named Albert who bore such a good resemblance in the grainy black-and-white shot taken by an insomniac dog walker that he gave a mother hope for three whole days. Albert was snapped outside a public toilet in a seaside caravan park at 2am. He happened to be only130 centimetres tall and was remarkedly aged, so that his hair had turned completely white from its once dark brown. A much taller man was with him, and these guys suffered unfair scrutiny for a while until their mutual attraction adequately explained why they were in that location at that hour.

There were many more children than adults, of course, in the lookalike images. Some boys, some girls. In most cases, they were being cared for at the time by a parent who just happened to be getting a coffee at the kiosk, or was changing a younger sibling’s nappy on a nearby bench, or was chasing a runaway dog, or was making a phone call in the car. In some cases, the children were playing hookey and as a result of being caught got into trouble with their school or their kindergarten or their parents or other authorities, but no harm done.

There was the case of the dark-haired 14-year old, Max, who was found passed out from a heroin overdose in tea tree scrub, not far from the scene of Albert’s adventures. Max had not been reported missing yet. In fact, he’d just had time to jump out of his bedroom window, meet his dealer and secure his gear, inject himself, then O.D. when he was found. Paramedics in the search party – this was in our first week – revived him and, as far as I know, he has gone on to live an uneventful life. It was lucky for Max that the search was on. We call him the silver lining.

But enough about the false trails. The fact remains that none of those hundreds of lookalikes was our boy. After so long, I have to accept – so the counselors tell me – that not one of them was, is or ever will be Matthew Clay Robinson, who might also have answered to Matt or Mattie or my little man.

Photo: CobraVerde

Bird call

On the phone last night to a friend,

On the phone last night to a friend,

Looking out across rooves as I

Complained about the new arrangements at work again,

I saw a silhouette

Against the neighbour’s lamplit window.

*

Black shape of a large bird

– perched on an aerial –

Framed in the golden square.

*

‘So after the meeting I thought fuck you , of course, and then he –’

Twisted its head and preened feathers,

Sat as still as stone,

Spread a powerful wingspan,

Lifted and was gone.

*

‘Well, if he thinks I’m going to come around to –’

A fluttering caught my eye.

The wings so much grander than the usual pigeon’s

And anyway, no pigeon in the dark.

A bat? But the feathers, the box-shaped tail.

*

Now, in my own yard,

Landed on the Hills Hoist,

Swayed, talons gripped the wire –

Its round head swiveled as if in a socket

Pale face – an owl.

*

What message from the wild?

This wildness I’ve never seen here –

Never in more than 40 years of city life, tram stops, supermarket shopping.

‘Sorry? Look, I have to go. See you at book club, yeah.’

*

The clothesline bare and bouncing.

Flown while I was hanging up.

Then a distant trombone note

And another, far away.

What message from the night’s great hunter?

What message?

Am I, as usual, too late to know?

***

I wrote this poem the other night. Feedback welcome.

Should your f#%king characters swear?

In the opening paragraph of John Marsden’s young adult novel Tomorrow When the War Began, Ellie, the teenaged main character, is trying to write down the story to come. She is not religious or a goody-goody or anymore a school girl. In fact, she’s a stressed-out rebel outcast who has ditched all authority in her life. Surrounded by her teenaged mates who are jostling and annoying her, she says, ‘Rack off guys!’

Now, I ask you, is that realistic?

I love John Marsden’s book with a passion, but the total lack of swearing doesn’t work for me. I know plenty of people like Ellie (I mean teenagers, not guerrillas). They all swear – maybe not in front of their grandmothers, but on their own and with their friends, and particularly when under stress. I too swear every day of my life and have done since I was younger than Ellie. I know I’m not alone in this.

Swearing is not a lazy way of being angry.

It’s learned as part of developing a grown-up language. It’s about being fluent. It’s about casual and easy communication. It’s about being in control, being independent of authority figures – particularly parents – who tell you how to speak. It’s normal, it’s a habit. And some people swear a lot, because of their upbringing, their circumstances or their personality. Yes, there are other inventive ways to abuse people, and express anger, fear, delight or pain. Swearing is not instead of but in addition to these ways.

And who says it’s offensive?

There’s a big question here about the morality of disallowing swearing and the constraints on culture when certain words are taboo or even defined as offensive. Look at who is being suppressed, and by whom.

As for stamping out or even keeping in check undesirable behaviour…

Radio stations forbid swearing on air, but shock jocks still manage to, uh, shock people. Unruly louts cower everyone in the train carriage by yelling out, ‘Cunts!’ Would it actually be any better if they yelled, ‘Vaginas!’? And do we really violate children by telling ‘shit’ instead of ‘poop’ jokes? Only when those children have been taught that ‘shit’ is a baaaad word, surely. When The Little Red School Book came out in 1969, my sister stole our copy from home and brought it to school to share under the desks. Everyone tittered over the similes for ‘penis’. That frisson was exactly what the ban-the-book campaigners wanted to prevent, but they would have had more success by introducing ‘dick’ and ‘cock’ into their own speech. Then we would have known that swearing was uncool.

So what does this mean for your fictional characters?

Are you going to give them authentic voices or shush them as if you’re a school librarian? Because if they always have to be on their best behaviour, you’re never going to see their real selves, just as you wouldn’t see their real selves in real life. So let them swear – it’s natural! Or more importantly, if your characters are the swearing types, it could sound unnatural if they don’t swear.

‘Darn it, Mac! You left the flipping gun in the truck. You’re such a so-and-so!’

‘Oh poo, Robbo! It wasn’t my blasted job to bring the silly gun, you dingbat!’

In my novel Wombat Blues, a tale told by a modern Australian teenage guy beset by troubles, my favourite line comes at the end of a long day when he’s hit rock bottom. He simply says, ‘Fuck. Fuck. Fuck. Fuck. Fuck.’ Totally sums it up, in my opinion.

But perhaps you don’t buy my arguments for swearing.

Still shaking your head? ‘I may not be the school librarian,’ I hear you say, ‘but I want to get my fucking novel into school libraries, so it’s got to pass the bloody librarians, doesn’t it?’

Okay, okay. So here are some creative alternatives.

- Pretend swearing: ‘Billions of blue blistering barnacles in a thundering typhoon!’

This is a great one for the kiddies and the kiddies-at-heart (and the librarians). Tintin, the famous boy reporter created by Hergé, has a best friend called Captain Haddock, an old sea dog who’s picked up the lingo. He loses his temper easily and loudly and says things like, ‘Who’s the thundering son of a sea-gherkin who did that?’ You just know what the translation would be in a Hollywood action film.

- Made-up words: ‘You puggin mother-pugger!’

Xavier Herbert’s Poor Fellow My Country is a novel about Aboriginal Australia. It’s an authentic and incendiary story about an unhappy period of Australian history when children were taken from their mothers simply for being ‘half-caste’. Herbert, who had worked in a ‘half-caste home’, wrote from deep personal experience about his huge cast of characters, and it shows. But nowhere in 1,500 pages does he use the ‘f’ word. It doesn’t seem to matter. Once you hear it a few times, you forget that he made up ‘pugging’ as an alternative. Whenever I read this book, I go around for weeks afterwards being misunderstood. (‘Who left the pugging milk out of the fridge?’ ‘What?’)

- Masked words: ‘effing’, ‘adjectival’

This is Peter Carey’s choice in True History of the Kelly Gang. Carey wrote his novel in Ned Kelly’s voice, and as all Australians know, Ned hated troopers but would have sworn like one. Still, Carey brought Ned to life without having him swear. He did it by giving the semi-literate bushranger the task of winning over his gentle readers with respect as well as honesty. Ned’s story is blunt and brutal, but he will not stoop to crudeness. There is power and, at the same time, restraint in the language. ‘It is death by hanging you little eff.’ ‘O Christ said he can’t a man eat his adjectival tea.’

(By the way, am I the only one who thought it was weird when Uncle Vernon muttered, ‘Enough – effing – owls’ in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix? After four long books, she finally made a character swear, and Uncle Vernon of all people… )

Photos:

Angry young man, by Frederic Dupont

Captain Haddock Anger Management Lessons, Ivan Rojas Reyes

…a man in the nineteenth century must and morally ought to be pre-eminently a characterless creature; a man of character, an active man is pre-eminently a limited creature. That is my conviction of forty years.

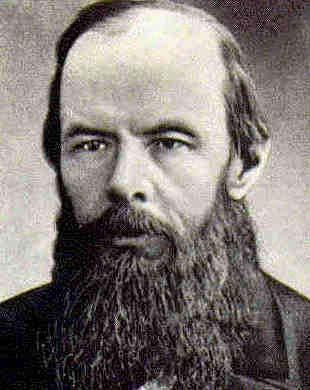

Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground is a short, strange, violent novel: a piece of 19th Century Russian punk.

Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground is a short, strange, violent novel: a piece of 19th Century Russian punk.

It’s well-known as a political and philosophical treatise and claimed as the earliest existentialist fiction. An unnamed narrator, a retired civil servant living in isolation and inaction – an ‘underground’ life – in St Petersburg, begins thus: ‘I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man.’ And it’s a ‘nasty, stinking, underground home’ that Dostoevsky describes with hot fury against the ‘literary’ world, the ‘decent’ world, and as he says, ‘whether you care to hear it or not’. Feel the spittle on your cheek when he announces the mood of this novel:

I got to the point of feeling a sort of secret abnormal, despicable enjoyment in returning home to my corner on some disgusting Petersburg night, acutely conscious that that day I had committed a loathsome action again, that what was done could never be undone, and secretly, inwardly gnawing, gnawing at myself for it, tearing and consuming myself till at last the bitterness turned into a sort of shameful accursed sweetness, and at last – into positive real enjoyment!

But for me, it’s one of the great how-to books on creating character.

I believe Dostoevsky intended it that way, and Underground man is presented as his model. (The character continuously talks about how ‘bookish’ he is, and not only how he’s read a lot of books. ‘I could not speak except “like a book”,’ he says, and adds, ‘it’s hardly literature so much as a corrective punishment.’)

Dostoevsky’s motivation is clear in the Notes as he rails against conventional literature, described as dreams instead of reality, those ‘flights into the sublime and the beautiful’, ‘fantastic love … never applied to anything human in reality’. He ponders what Underground man would look like if he were instead a conventional literary hero (‘passed satisfactorily by a lazy and fascinating transition into the sphere of art’). He’d be ‘triumphant over everyone’ and they’d all be forced to recognize his superiority, although he’d also be humble. He’d come in ‘for countless millions’ then immediately donate them ‘to humanity’. While everyone adored him, he’d ‘go barefoot and hungry preaching new ideas and fighting a victorious Austerlitz [famous Napoleonic battle] against the obscurantists’.* In other words, he’d be unrealistic and ridiculous… but also recognizable as the main character of much bad fiction.

What attributes does Dostoevsky give his ‘characterless’ character?

- A contrary nature that can’t be pinned down to one set of motives

Underground man is a mass of contradictions:

You thirst for life and try to settle the problems of life by a logical tangle. And how persistent, how insolent are your sallies, and at the same time what a scare you are in! You talk nonsense and are pleased with it; you say impudent things and are in continual alarm and apologizing for them. You declare that you are afraid of nothing and at the same time try to ingratiate yourself in our good opinion… You may, perhaps, have really suffered, but you have no respect for your own suffering. You may have sincerity, but you have no modesty… You boast of consciousness, but you are not sure of your ground…

But what does this contrariness mean in practice? Well, take, for example, revenge. The ‘direct’ and ‘stupid’ person (conventional hero) ‘dashes straight for his object like an infuriated bull with its horns down’. Underground man, however, who thinks of himself as a mouse, creates ‘so many other nastinesses in the form of doubts and questions, adds to the one question so many other unsettled questions that there inevitably works up around it a sort of fatal brew… Maybe it will begin to revenge itself, too, but, as it were, piecemeal, in trivial ways, from behind the stove, incognito, without believing either in its own right to vengeance, or in the success of its revenge, knowing that from all its efforts at revenge it will suffer a hundred times more than he on whom it revenges itself…’

So Underground man is definitely not happy, but lest you imagine that he is also evil, we’re reminded that – good or bad – everyone is full of guilty, fearful, secret thoughts. In fact, ‘the more decent he is, the greater the number of such things in his mind.’

- Choice – reaching beyond the rational

It goes deeper than giving a character a range of qualities. A person is ‘not a piano-key!’ Underground man doesn’t always act to his own advantage. More important than reason is choice:

And one may choose what is contrary to one’s own interests, and sometimes one positively ought (that is my idea). One’s own free unfettered choice, one’s own caprice, however wild it may be, one’s own fancy worked up at times to frenzy… And choice, of course, the devil only know what choice.

- A surface but also an underground

This character is a thinker, and we are privy to his inner, ‘underground’ world. But his thoughts are not always reliable and honest. In fact, he’s a liar and even lies to himself – even when he’s telling us so.

I swear to you, gentlemen, there is not one thing, not one word of what I have written that I really believe. That is, I believe it, perhaps, but at the same time I feel and suspect that I am lying like a cobbler.

- Above all, an individual human nature

Underground man is ‘a real individual body and blood’, as opposed to ‘some sort of generalized man.’ His life, according to his own view, is ‘paltry, unliterary, commonplace.’ (Unliterary = unromantic)

Okay, he’s not very nice. So why should you try to create such a creature?

Because no one is more interesting or real. We’re fascinated by Underground man – and woman! We don’t like to read about nice people, we don’t believe them, unless we at least glimpse a bit of nasty underneath. Look at the examples below. These characters are so different, but we recognise ourselves in them – villains and heroes all. That’s their power. Underground man dismisses the retort, ‘Speak for yourself.’ If we’re tempted to write him off as an oddball, he warns: ‘I have only in my life carried to an extreme what you have not dared to carry halfway, and what’s more, you have taken your cowardice for good sense, and have found comfort in deceiving yourselves.’ This is not a creature without character but without a definable character because it is as vast as any real human one.

Examples of ‘characterless’ characters

:

Raskolnikov Dostoevsky used his own instructions some years later to create the main character of Crime and Punishment, arguably one of the greatest anti-heroes in all literature. Raskolnikov commits murder and spends most of the novel trying to work out why.

:

Hamlet Of course, Dostoevsky’s example of the revenge motive immediately calls to mind Shakespeare’s deepest role. Underground man does not have to be ignoble.

:

Catherine Earnshaw The tragic centre of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Wild and wayward, yet loyal in love even beyond the grave.

:

Anna Karenina Another tragic heroine. Adores her only son then abandons him for a love affair that ends in suicide.

:

Victor Maskell A modern one, the subject of John Banville’s 1997 novel, The Untouchable. He’s the classic unreliable narrator, a double agent based on the real-life spy Anthony Blunt, a cad, mean to his children, charming, a hopeless romantic.

:

Chip Lambert Another modern one, from Jonathan Franzen’s 2001 novel The Corrections. On the surface, an ordinary middle class academic failure. Underneath/underground, a depressive, outrageously irresponsible, unjust to his parents. Also, like the rest of the Lamberts, sad, lovable and funny, and we’re glad he has a happy ending.

How do you create this character?

Clearly not by writing a list of traits or answering a set of stock questions: What’s their favourite food? Who do they vote for? What was their most loved pet? As if you’re crafting a profile on a dating site. You simply can’t capture this character in any plan. Well then, how? Here’s an idea.

Write an incident – a small one – in your Underground wo/man’s life. Start with one of the following:

- Their voice

- Their mood

- An image – of something specific, tiny or off to the side.

Be very honest with yourself about what is going on. Don’t worry if Underground wo/man isn’t. Just let them do what they do.

* By the way, Dostoevsky was an avowed ‘obscurantist’. He saw human doubt and confusion as immensely valuable, and this was in fact the basis of his strong religious faith. The theme is borne out in The Brothers Karamazov. I’m grateful to In Umbris Sancti Petri, a blog on Catholicism and philosophy, for alerting me to the following from Dostoevsky’s diary: “The dolts have ridiculed my obscurantism,’ writes Dostoevsky concerning The Brothers Karamazov, ‘and the reactionary character of my faith. These fools could not even conceive so strong a denial of God as the one to which I gave expression…The whole book is an answer to that. You might search Europe in vain for so powerful an expression of atheism. Thus it is not like a child that I believe in Christ and confess him. My hosanna has come forth from the crucible of doubt.’

Photos:

Dostoevsky, Douglas Brown

Axe murder (Raskolnikov), Jacob Enos

Hamlet, Stephen Boisvert

Catherine in Wuthering Heights, Jason Paul Smith

Anna Karenina, Cod Gabriel

The spy, Marcus S.

Jonathan Franzen, David Shankbone

A Smile of Fortune by Joseph Conrad – a gay classic

I’m excited to announce the induction of Joseph Conrad’s story ‘A Smile of Fortune’ into the annals of classic literature with unrecognized gay sub-texts. This hall of fame (but not for being gay) includes Shakespeare’s The Taming of The Shrew and Astrid Lingren’s The Brothers Lionheart, as I’ve already argued. Conrad’s story is a serious addition and way up the list.

This post might also be a scoop because I’ve failed to uncover any other writing on Conrad that even hints at a gay sub-text in ‘A Smile of Fortune’. It’s tempting to think that I must therefore be wrong. Yet a gay reading would explain the weird plot and mysterious characters, and other commentary on ‘A Smile of Fortune’ tends to leave it as mysterious or skips over the mysterious elements altogether. So please bear with this rather long post in which I explain.

I trust that you’ll find the story crafty and intriguing. Whether or not you care at all about gay sub-texts, it’s a fascinating puzzle.

Conrad, the gay writer

When it suits me, I’m happy to invoke Roland Barthes’s famous essay to dismiss as irrelevant the author’s intention for their story. So what if the author never had a gay thought and would possibly even disagree vehemently with me about his or her own work? Once the words leave your quill or typewriter, mate, they belong to me, and I’ll read them as I see fit. (I had to take that attitude with The Taming of the Shrew, frankly.)

However, in the case of ‘A Smile of Fortune’, I can turn to Conrad himself for support. A review of his life shows that he was probably straight – romantically attached to women, happily married. But he was a sailor, and his biography The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad demurely refers to the possibility of ‘situational homosexuality’ at sea. Certainly, Conrad sometimes met and befriended gay men, and some of his strongest characters are homosexual, based on real people and situations, as he himself admitted. This was the case, for example, with Mr Jones the villain of Victory, and Il Conde, a tale about male prostitution. But the best evidence comes from the sheer fact that all Conrad’s writing shows a fascination with hidden motives, and he often wrote subtle psychological sub-texts. He would have loved for ‘A Smile of Fortune’ to have a secret gay hull!

The plot

For those who haven’t yet read the story, here’s a synopsis. It was written in 1910, but we can assume it’s set in the late 1800s because the characters are loosely based on people Conrad met in Mauritius at that time.

A young sea captain arrives in a port town to trade. Immediately, he is accosted by a chandler (seller of ships’ provisions) named Jacobus who proceeds to wheedle his way into the captain’s trust.

I took stock of a big, pale face, hair thin on the top, whiskers also thin, of a faded nondescript colour, heavy eyelids.

It so happens that the captain has been asked by his ship’s owners to look up a merchant named Jacobus in the town. The chandler Jacobus admits that he is not the merchant Jacobus but his brother, and he tells the captain, ‘My brother’s a very different person.’ Acquaintances of the captain confirm that there are indeed two brothers Jacobus, the chandler being a disreputable social outcast while the merchant is wealthy and well-respected. The two have apparently not spoken to each other for years.

The captain calls on the merchant Jacobus, according to his owner’s instructions. He is greatly surprised to find that this supposedly wealthy merchant has a squalid office away from the business quarter. In an outer room he first meets the merchant’s assistant, a ‘mulatto’ boy, who admits him with strange trepidation into the merchant’s inner office.

A lanky, inky, light-yellow, mulatto youth, miserably long-necked and generally recalling a sick chicken…

The merchant is violent and menacing both to the boy and the captain, who is offended and quickly leaves. The boy looks like a Jacobus, and the captain realises that he must be related to and is probably the son of the abusive merchant, who himself looks like his chandler brother. From this incident, the captain decides that it is the merchant rather than the chandler who is the ne’er-do-well Jacobus, contrary to general opinion.

Meanwhile, the chandler is manipulating the naïve young captain to do business with him. The captain is lured to the chandler’s house ostensibly so that they may talk privately, but while waiting there for the chandler, the captain meets a young woman named Alice, the chandler’s daughter. The story accepted in the town is that Alice is an offspring of the chandler’s unseemly liaison with a travelling circus woman, who long ago died and left him with the child. Although Alice mainly ignores and is rude to the captain, he becomes entranced with her and returns again and again to the chandler’s house just to see her. Indeed, it’s the only place he can see her because she, like her father, is a social outcast and never ventures out.

A sort of shady, intimate understanding seemed to have been established between us.

On a visit to the house just before his ship is due to sail, the captain is no longer able to resist temptation and grabs Alice for a kiss. She pushes him away and runs off, whereupon the chandler walks in and picks up the shoe which Alice has dropped in her haste. In what appears to be veiled blackmail, the chandler advises the captain to buy a large shipload of potatoes from him. This is the business deal the chandler has been attempting all along. The captain agrees in order to avoid scandal – ‘outward decency may be bought too dearly at times’, although he believes the transaction spells commercial disaster.

He sees Alice once more at a parting in which both of them have changed. Neither has any passion left, either desire or anger. He’s off, and she’s done her job.

Unexpectedly, the potatoes deal is profitable for the captain, although he remains dispirited as he travels on. A letter arrives from his ship’s owners inviting him to return to the port town to do further trade on the basis that ‘our good friend’ the merchant Jacobus has been in touch to say that he and the captain actually ‘hit it off’.

But the captain is consumed by self-disgust about his dealings with the Jacobus family, particularly as he remembers that Alice actually returned his kiss, and he vows to himself never to return ‘to fan that fatal spark’. Depressed and appalled by his memories, he finally gives up his ship.

… the fact is that the Indian Ocean and everything that is in it has lost its charm for me.

The cunning sub-plot

So here’s my thesis. The mulatto son of the merchant Jacobus, and Alice, the so-called daughter of the chandler Jacobus, are the same person – a young man. This youth is actually the bastard son of the chandler, who is in cahoots with his brother to entrap the captain.

Chandler Jacobus elicits from the captain in their first meeting that the captain is ‘neither married nor even engaged’. While the captain is inwardly shuddering at the very thought, the chandler takes note and concludes – rightly – that the captain may be lured by a boy dressed as a girl.

^

… he asked me with a dental, shark-like smile – if sharks had false teeth – whether I had yet made my little arrangements for the ship’s stay in port.

But the captain nearly wrecks the plan by turning up unexpectedly at the merchant Jacobus’s office. He wasn’t supposed to meet the mulatto youth out of the Alice costume, but there he is, and the youth faces the captain ‘as if gone dumb with fright’. Understandably so, as the youth know he’s been caught out. Also, he’s an unhappy pawn in the Jacobus game. The merchant is indeed disgusted by and therefore abusive towards his brother’s offspring. But the quick-thinking merchant saves the situation by hustling the captain out as quickly as possible with extreme rudeness, before the captain can gain more than a glimpse of the youth.

And why the shabby office? The merchant plays cards – and we may presume, does business – with the gentry at his nice house. He generally discourages visitors to the office, where he keeps the boy. Neither ‘Alice’ nor the boy is ever seen in public, in case people discover that they’re one and the same. After all, it’s likely that the captain is not the first patsy to be taken in by the Jacobus brothers’ trick.

Later, at the chandler’s house, the mulatto youth is dressed up as ‘Alice’ in time for the captain’s visit there. Alice has a ‘mass of black, lustrous locks’ that sits awkwardly on her head (a wig) and powder on her face. She wears ‘a wrapper of some thin stuff’, never described as a dress, which reveals a ‘young supple body’. As his enchantment increases over the weeks, the captain notices many things about this body. Alice has a ‘round, strong neck’, a ‘generous, fine, somewhat masculine hand’, and ‘an unexpectedly harsh voice’. There is ‘something elusive and defiant in her very form’. Just like the mulatto youth, she bears the unmistakeable Jacobus looks, including the same dark eyes. Never does the captain mention or even appear to notice whether Alice has any female curves.

The naïve young sea dog is unaware – and to tell the truth, a bit thick – about the affairs of his own heart. He’s also a late 19th Century gentleman, very proper and upstanding, so has an excuse. All he knows is that he and Alice have ‘the bond of an irrealizable desire’. He muses that the earth is ‘the abode of obscure desires, of extravagant hopes, of unimaginable terrors’ as he gazes over Alice’s androgynous lines.

What folly was this? I would ask myself. It was like being the slave of some depraved habit.

Meanwhile, the poor youth is becoming enamoured of the captain too, although ‘she’ is under strict instructions to hold him off as long as possible until he can be properly caught in the act of doing something to her. She tries to warn him. ‘It’s false,’ Alice says in the middle of one of their pointless conversations, but he doesn’t get it. Later, after the kissing, and after the captain has been manoeuvred into the potatoes deal, Alice reveals more. ‘I am not afraid of papa – by himself,’ she says, and adds, ‘I am not afraid of you!’ So, who then, in conjunction with ‘papa’, the chandler, does she fear? It can only be the chandler’s merchant brother, who is so abusive to her when she is his boy servant.

Ultimately, the captain is the one who’s afraid. He leaves, admitting that ‘only a sense of my dignity prevented me fleeing headlong from that catastrophic revelation.’ He is pursued, of course, by the brothers who want to use him further, but mainly by that revelation. It had been ‘a unique sensation which I indulged with dread, self-contempt, and deep pleasure’, but he’s not strong enough to own it, let alone go back to Alice, and so he gives up his ship and the sea. In the end, he knows himself as ‘vanquished’.

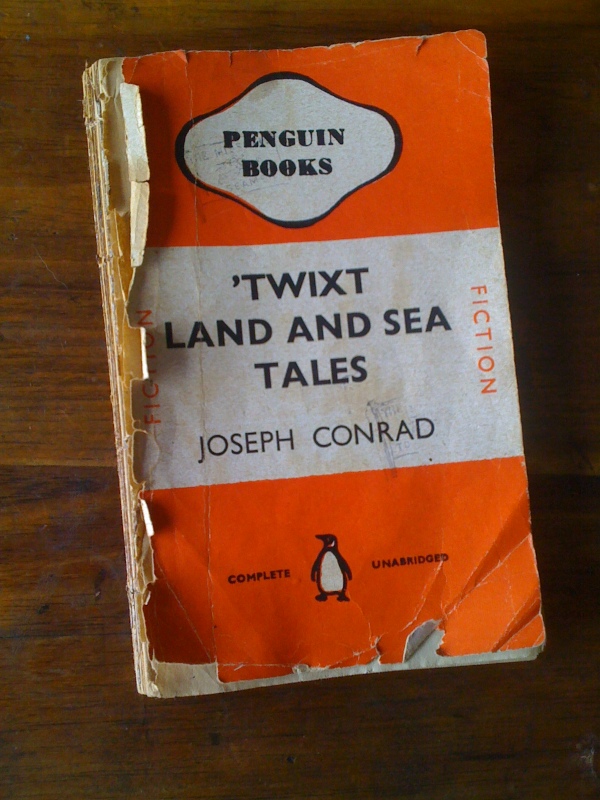

‘Twixt Land and Sea

My own copy of the original Penguin paperback published in 1943, covered in stamps from 'The Mission for Seamen' and containing ads for Cadbury Bournville Cocoa and Chappie dog food

So which reading of ‘A Smile of Fortune’ do you prefer? The usual one in which Alice is a girl, based on Alice Shaw, who Conrad met in Mauritius as a young man? Or mine in which Alice is actually the ‘miserable mulatto lad’? If you don’t like my theory, then at least ponder the following:

- The dramatic scene in the merchant’s office must serve some purpose in the story. If this short novella is just about the captain being blackmailed by the chandler over his daughter, why include the merchant Jacobus and the mulatto youth at all? Remember, Conrad was a master and can be trusted to have had his reasons for writing them in.

- If Alice is a girl, the ending to the story is ambiguous. Neither the captain nor the reader can really understand why he’s so deeply appalled by his dealings with the Jacobus family. You might say, well, that’s just typically modernist. But, but, but… Conrad’s writing actually harks back to an earlier time of adventure when characters had motives and stories worked out.

- And was it really accidental that ‘A Smile of Fortune’ was first published in book form in a collection of Conrad’s stories called ‘Twixt Land and Sea Tales? (Betwixt and between, neither one nor the other.) The very next story in the collection is ‘A Secret Sharer’, about a captain who beds down with a stowaway sailor. There are clear sexual connotation in that one, at least.

I could go on and give you more evidence (and all right, conjecture and innuendo too) but – please – read it and judge for yourself. And do let me know what you think.

Photos:

Joseph Conrad, drawing and books: Ben Sutherland

Mauritius: Selene Weijenberg

Joanna Mary Boyce: Head of a Mulatto Woman: freeparking