A Smile of Fortune by Joseph Conrad – a gay classic

I’m excited to announce the induction of Joseph Conrad’s story ‘A Smile of Fortune’ into the annals of classic literature with unrecognized gay sub-texts. This hall of fame (but not for being gay) includes Shakespeare’s The Taming of The Shrew and Astrid Lingren’s The Brothers Lionheart, as I’ve already argued. Conrad’s story is a serious addition and way up the list.

This post might also be a scoop because I’ve failed to uncover any other writing on Conrad that even hints at a gay sub-text in ‘A Smile of Fortune’. It’s tempting to think that I must therefore be wrong. Yet a gay reading would explain the weird plot and mysterious characters, and other commentary on ‘A Smile of Fortune’ tends to leave it as mysterious or skips over the mysterious elements altogether. So please bear with this rather long post in which I explain.

I trust that you’ll find the story crafty and intriguing. Whether or not you care at all about gay sub-texts, it’s a fascinating puzzle.

Conrad, the gay writer

When it suits me, I’m happy to invoke Roland Barthes’s famous essay to dismiss as irrelevant the author’s intention for their story. So what if the author never had a gay thought and would possibly even disagree vehemently with me about his or her own work? Once the words leave your quill or typewriter, mate, they belong to me, and I’ll read them as I see fit. (I had to take that attitude with The Taming of the Shrew, frankly.)

However, in the case of ‘A Smile of Fortune’, I can turn to Conrad himself for support. A review of his life shows that he was probably straight – romantically attached to women, happily married. But he was a sailor, and his biography The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad demurely refers to the possibility of ‘situational homosexuality’ at sea. Certainly, Conrad sometimes met and befriended gay men, and some of his strongest characters are homosexual, based on real people and situations, as he himself admitted. This was the case, for example, with Mr Jones the villain of Victory, and Il Conde, a tale about male prostitution. But the best evidence comes from the sheer fact that all Conrad’s writing shows a fascination with hidden motives, and he often wrote subtle psychological sub-texts. He would have loved for ‘A Smile of Fortune’ to have a secret gay hull!

The plot

For those who haven’t yet read the story, here’s a synopsis. It was written in 1910, but we can assume it’s set in the late 1800s because the characters are loosely based on people Conrad met in Mauritius at that time.

A young sea captain arrives in a port town to trade. Immediately, he is accosted by a chandler (seller of ships’ provisions) named Jacobus who proceeds to wheedle his way into the captain’s trust.

I took stock of a big, pale face, hair thin on the top, whiskers also thin, of a faded nondescript colour, heavy eyelids.

It so happens that the captain has been asked by his ship’s owners to look up a merchant named Jacobus in the town. The chandler Jacobus admits that he is not the merchant Jacobus but his brother, and he tells the captain, ‘My brother’s a very different person.’ Acquaintances of the captain confirm that there are indeed two brothers Jacobus, the chandler being a disreputable social outcast while the merchant is wealthy and well-respected. The two have apparently not spoken to each other for years.

The captain calls on the merchant Jacobus, according to his owner’s instructions. He is greatly surprised to find that this supposedly wealthy merchant has a squalid office away from the business quarter. In an outer room he first meets the merchant’s assistant, a ‘mulatto’ boy, who admits him with strange trepidation into the merchant’s inner office.

A lanky, inky, light-yellow, mulatto youth, miserably long-necked and generally recalling a sick chicken…

The merchant is violent and menacing both to the boy and the captain, who is offended and quickly leaves. The boy looks like a Jacobus, and the captain realises that he must be related to and is probably the son of the abusive merchant, who himself looks like his chandler brother. From this incident, the captain decides that it is the merchant rather than the chandler who is the ne’er-do-well Jacobus, contrary to general opinion.

Meanwhile, the chandler is manipulating the naïve young captain to do business with him. The captain is lured to the chandler’s house ostensibly so that they may talk privately, but while waiting there for the chandler, the captain meets a young woman named Alice, the chandler’s daughter. The story accepted in the town is that Alice is an offspring of the chandler’s unseemly liaison with a travelling circus woman, who long ago died and left him with the child. Although Alice mainly ignores and is rude to the captain, he becomes entranced with her and returns again and again to the chandler’s house just to see her. Indeed, it’s the only place he can see her because she, like her father, is a social outcast and never ventures out.

A sort of shady, intimate understanding seemed to have been established between us.

On a visit to the house just before his ship is due to sail, the captain is no longer able to resist temptation and grabs Alice for a kiss. She pushes him away and runs off, whereupon the chandler walks in and picks up the shoe which Alice has dropped in her haste. In what appears to be veiled blackmail, the chandler advises the captain to buy a large shipload of potatoes from him. This is the business deal the chandler has been attempting all along. The captain agrees in order to avoid scandal – ‘outward decency may be bought too dearly at times’, although he believes the transaction spells commercial disaster.

He sees Alice once more at a parting in which both of them have changed. Neither has any passion left, either desire or anger. He’s off, and she’s done her job.

Unexpectedly, the potatoes deal is profitable for the captain, although he remains dispirited as he travels on. A letter arrives from his ship’s owners inviting him to return to the port town to do further trade on the basis that ‘our good friend’ the merchant Jacobus has been in touch to say that he and the captain actually ‘hit it off’.

But the captain is consumed by self-disgust about his dealings with the Jacobus family, particularly as he remembers that Alice actually returned his kiss, and he vows to himself never to return ‘to fan that fatal spark’. Depressed and appalled by his memories, he finally gives up his ship.

… the fact is that the Indian Ocean and everything that is in it has lost its charm for me.

The cunning sub-plot

So here’s my thesis. The mulatto son of the merchant Jacobus, and Alice, the so-called daughter of the chandler Jacobus, are the same person – a young man. This youth is actually the bastard son of the chandler, who is in cahoots with his brother to entrap the captain.

Chandler Jacobus elicits from the captain in their first meeting that the captain is ‘neither married nor even engaged’. While the captain is inwardly shuddering at the very thought, the chandler takes note and concludes – rightly – that the captain may be lured by a boy dressed as a girl.

^

… he asked me with a dental, shark-like smile – if sharks had false teeth – whether I had yet made my little arrangements for the ship’s stay in port.

But the captain nearly wrecks the plan by turning up unexpectedly at the merchant Jacobus’s office. He wasn’t supposed to meet the mulatto youth out of the Alice costume, but there he is, and the youth faces the captain ‘as if gone dumb with fright’. Understandably so, as the youth know he’s been caught out. Also, he’s an unhappy pawn in the Jacobus game. The merchant is indeed disgusted by and therefore abusive towards his brother’s offspring. But the quick-thinking merchant saves the situation by hustling the captain out as quickly as possible with extreme rudeness, before the captain can gain more than a glimpse of the youth.

And why the shabby office? The merchant plays cards – and we may presume, does business – with the gentry at his nice house. He generally discourages visitors to the office, where he keeps the boy. Neither ‘Alice’ nor the boy is ever seen in public, in case people discover that they’re one and the same. After all, it’s likely that the captain is not the first patsy to be taken in by the Jacobus brothers’ trick.

Later, at the chandler’s house, the mulatto youth is dressed up as ‘Alice’ in time for the captain’s visit there. Alice has a ‘mass of black, lustrous locks’ that sits awkwardly on her head (a wig) and powder on her face. She wears ‘a wrapper of some thin stuff’, never described as a dress, which reveals a ‘young supple body’. As his enchantment increases over the weeks, the captain notices many things about this body. Alice has a ‘round, strong neck’, a ‘generous, fine, somewhat masculine hand’, and ‘an unexpectedly harsh voice’. There is ‘something elusive and defiant in her very form’. Just like the mulatto youth, she bears the unmistakeable Jacobus looks, including the same dark eyes. Never does the captain mention or even appear to notice whether Alice has any female curves.

The naïve young sea dog is unaware – and to tell the truth, a bit thick – about the affairs of his own heart. He’s also a late 19th Century gentleman, very proper and upstanding, so has an excuse. All he knows is that he and Alice have ‘the bond of an irrealizable desire’. He muses that the earth is ‘the abode of obscure desires, of extravagant hopes, of unimaginable terrors’ as he gazes over Alice’s androgynous lines.

What folly was this? I would ask myself. It was like being the slave of some depraved habit.

Meanwhile, the poor youth is becoming enamoured of the captain too, although ‘she’ is under strict instructions to hold him off as long as possible until he can be properly caught in the act of doing something to her. She tries to warn him. ‘It’s false,’ Alice says in the middle of one of their pointless conversations, but he doesn’t get it. Later, after the kissing, and after the captain has been manoeuvred into the potatoes deal, Alice reveals more. ‘I am not afraid of papa – by himself,’ she says, and adds, ‘I am not afraid of you!’ So, who then, in conjunction with ‘papa’, the chandler, does she fear? It can only be the chandler’s merchant brother, who is so abusive to her when she is his boy servant.

Ultimately, the captain is the one who’s afraid. He leaves, admitting that ‘only a sense of my dignity prevented me fleeing headlong from that catastrophic revelation.’ He is pursued, of course, by the brothers who want to use him further, but mainly by that revelation. It had been ‘a unique sensation which I indulged with dread, self-contempt, and deep pleasure’, but he’s not strong enough to own it, let alone go back to Alice, and so he gives up his ship and the sea. In the end, he knows himself as ‘vanquished’.

‘Twixt Land and Sea

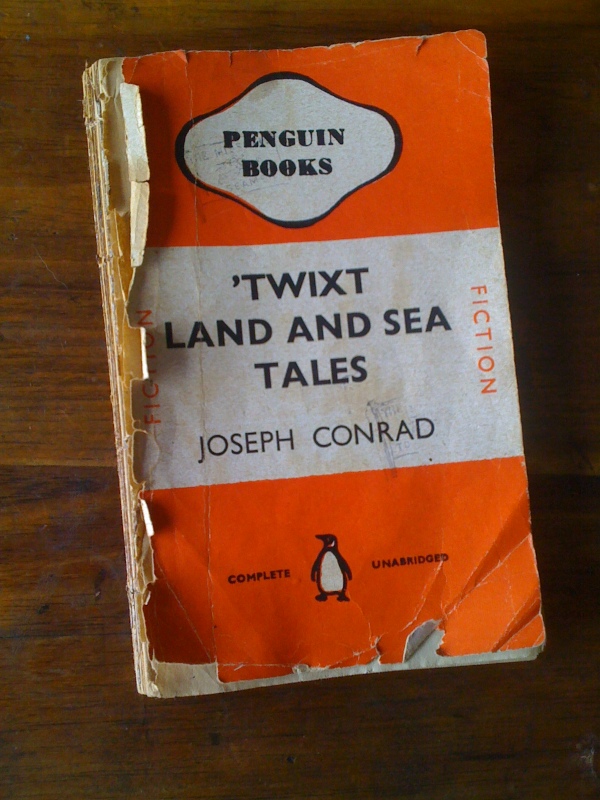

My own copy of the original Penguin paperback published in 1943, covered in stamps from 'The Mission for Seamen' and containing ads for Cadbury Bournville Cocoa and Chappie dog food

So which reading of ‘A Smile of Fortune’ do you prefer? The usual one in which Alice is a girl, based on Alice Shaw, who Conrad met in Mauritius as a young man? Or mine in which Alice is actually the ‘miserable mulatto lad’? If you don’t like my theory, then at least ponder the following:

- The dramatic scene in the merchant’s office must serve some purpose in the story. If this short novella is just about the captain being blackmailed by the chandler over his daughter, why include the merchant Jacobus and the mulatto youth at all? Remember, Conrad was a master and can be trusted to have had his reasons for writing them in.

- If Alice is a girl, the ending to the story is ambiguous. Neither the captain nor the reader can really understand why he’s so deeply appalled by his dealings with the Jacobus family. You might say, well, that’s just typically modernist. But, but, but… Conrad’s writing actually harks back to an earlier time of adventure when characters had motives and stories worked out.

- And was it really accidental that ‘A Smile of Fortune’ was first published in book form in a collection of Conrad’s stories called ‘Twixt Land and Sea Tales? (Betwixt and between, neither one nor the other.) The very next story in the collection is ‘A Secret Sharer’, about a captain who beds down with a stowaway sailor. There are clear sexual connotation in that one, at least.

I could go on and give you more evidence (and all right, conjecture and innuendo too) but – please – read it and judge for yourself. And do let me know what you think.

Photos:

Joseph Conrad, drawing and books: Ben Sutherland

Mauritius: Selene Weijenberg

Joanna Mary Boyce: Head of a Mulatto Woman: freeparking

I thought this was a joke at first but after re-reading the short piece last night I have to agree. It always seemed a crafty tale to me, as if I was being mislead for something that never came in the end. I’m going to go through it again and see if I can find anything to contradict the gay subtext.

Of course, it is a joke in a way. Who’s to say what the truth is – as with all conspiracy theories. You see what you want to see. I will be very interested to learn what you come up with to contradict the theory – or further confirm it! Please tell me.

You know, there has been at least one essay written about the presence of a gay subtext in Conrad’s work – and it included several of his most famous novels such as Nostromo and Lord Jim. I can’t remember who wrote it, but if you’re interested I could probably find it again for you.

I’ve read a little about gay subtexts in other stories by Conrad – some of them not so ‘sub’. I’d be very interested in an essay that deals with the subject. Thanks! I’m a big fan of his, and I presume you are too??

One such essay can be found here: http://www.oscholars.com/TO/Appendix/Library/RUPPEL.htm, and is fittingly entitled “Joseph Conrad and the Ghost of Oswar Wilde” 🙂

There are plenty more around, but none that I could easily find on the Internet… I’ll continue to check and send you the links should I find more.

I do love Conrad, but as I am currently writing my Master’s thesis on his works, I am close to the overdose right now 🙂

I thoroughly enjoyed this essay. It hints at something I have always felt, instinctively, about Conrad’s work. Your interpretation seems worthy of Conrad’s artistry whereas a more simplistic view seems incongruous with the complexity that we know and associate with his writing. Often people are criticized for retroactively “mining” works looking for gay subtext, but in a culture which is often harsh on gay people in general, the sublimation of gay themes and “code words” are really the only clues we have to what is likely the truer, more honest, intention of the author. Many thanks.

A kindred spirit! My thanks. Do you have any ideas about other stories that might be similarly mined?

I love it, not sure I agree, but it definitely is something to think about. There is precious little written about this particular story, and I’m in the process of putting together a scholarly essay on it. I will be re-reading to see what I come up with. It was fun, thanks!

Thanks, Laura! I’d love to see your essay – would you mind sending it to me when it’s finished? And if you have any arguments for or against, I’d really like to know.

I’d be happy to, it’s for an assignment and will be looking at Conrad through this story through the theories of a couple of my favorite psychological theorists.

Fran,

Where in Stape’s biography of Conrad did you find it “demurely refers to the possibility of ‘situational homosexuality’ at sea.” ?

Can’t remember – it’s been a while! I do remember that I had to search that book and others high and low for any reference to even the possibility that Conrad had personal experience.